* A video version of this race recap can be found on my YouTube channel here.

A triathlon is a game of contradiction.

You spend hours, weeks, months training for something that lasts moments of your life. Improve at one sport by mastering three. Train slower to race faster. Race slower to race faster. Do it alone, surrounded by people. Never see a finish line as the end.

One of the most challenging contradictions is the trap of identity. To do well, you have to immerse yourself in training for long periods of time. It can become you; consume you. And then what is objectively a meaningless act of physical exertion assumes a station in your life that it never deserved. And you are left with nothing but finish times and medals, to gather dust because nobody cares.

I thought about these contradictions a lot during my training for my first Ironman 70.3 race in Indian Wells – La Quinta California. It seemed fitting in this vein of contradiction that I would train in the cold and snow in order to race in the warm desert. I hoped that by recognizing the contradictions inherent in what I was doing, I could avoid that most challenging trap, and come away with an experience, rather than just another race.

After Musselman in July, I took a break for a few weeks, and then started training again. I had a few minor injuries, which were challenging, but for the most part my training was consistent. I did some bike fitting and got a set of aerobars on my bike. Winter arrived early in Vermont; we had snow on the ground before Thanksgiving. So most of my riding was indoors. I ran outside as much as I could. And weather doesn’t matter in the pool, of course.

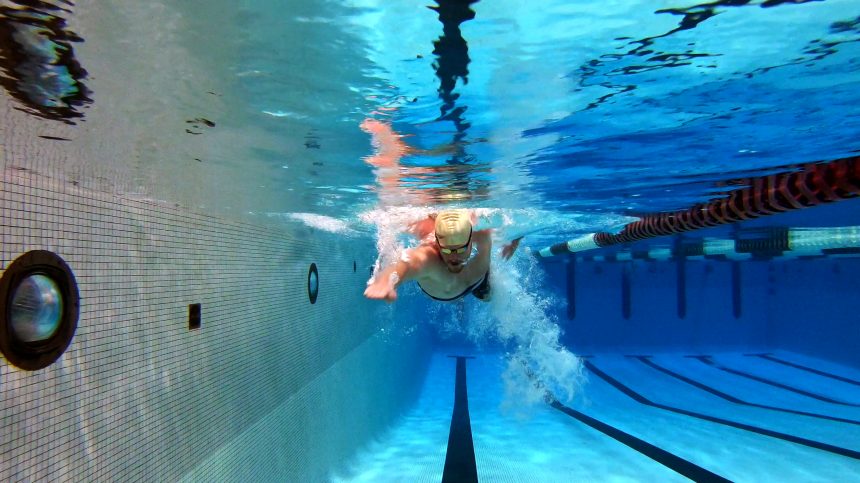

Swimming was a major area of focus for me this fall. I got a second swim analysis and really worked on my technique. I was able to take another ten seconds off my 100-yard time, and by December I was swimming faster on average than I ever had.

I had also been trying to eat smarter, both to be healthier and to drop extra weight. With the help of a friend, I definitely had some success here, though it added some stress to our family routine. Kids like what they like.

I was a little concerned about flying my bike to California, because I had only done it once before and I didn’t have to assemble it myself when I arrived that time. So I broke it down and packed it up at the bike shop so I could get guidance with questions that I had and hands-on help from Darren, my friend who owns Vermont Bicycle Shop. I felt a lot more confident once it was all ready to go.

The flights were pretty uneventful, and we made it to San Diego in one piece — including my bike. One of the first things I did was put it back together; I wanted to make sure I would have enough time to solve any problems that came up. Luckily, there didn’t seem to be any and the assembly went pretty smoothly.

We spent a few days with my brother’s family in San Diego, hiking at Torrey Pines and playing on the beach. It was a nice way to get acclimated to the environment. It wasn’t as warm as I thought it would be, but it definitely was a lot warmer than Vermont. Locals on the beach were dressed in winter coats and hats, but our girls thought it was the perfect weather for swimming in the Pacific.

Before long it was time to drive to Indian Wells. The amazing scenery on that drive took us all by surprise. We stopped for a moment but the day before the race was very busy so there wasn’t a lot of time for sight-seeing.

After getting the family settled at the hotel, I had my first Ironman athlete check-in experience and got to see the pro panel, which included the eventual race winners Lionel Sanders and Paula Findlay. I checked my run gear in to T2, a little overwhelmed by the enormity of the transition area. Then it was time for a half-hour drive to the swim start and T1, to see the swim course, check in my bike and decontaminate my wetsuit before hanging it on the racks where it would stay until race morning. I made sure to mark it well so I wouldn’t have any trouble finding it.

My day would have gone quite differently if it hadn’t been for my teammate Lacy. She and her husband gave me a lift to the shuttle buses, which was already a great help by itself, but when she mentioned her water bottles I realized I had forgotten something at the hotel. Specifically, all of my hydration. It was still sitting in my refrigerator. They drove me back so I could retrieve them and I was so grateful. Luckily we were up early enough that it didn’t affect our day — we got on a bus with no waiting and were off to the start area.

I knew the water would be cold. The reported temperature that morning was just under 59 degrees. There was no warm-up swim. We stood in line at the rolling start for a long time before finally getting into the water. And then, finally, after everything, I was racing.

The first one or two hundred meters were tough. I was hyperventilating from the shock of the water temperature and struggling to relax and find my rhythm. I expected that, but it didn’t make it any easier. Finally I settled in, though, and found my zone. It was clear pretty quickly that I should have seeded myself further forward; nobody around me was actually swimming at the pace they lined up for. I was crawling over people all the way. My goggles half-filled with water but I ignored it since I could still see. When I finally crawled out of the lake, I had a personal best time of 34 minutes. By my watch, I had swum ten seconds per 100 yards faster than my first 70.3 in July.

As I mounted my bike, I readied myself mentally to face the biggest contradiction of the day. I had programmed the wattage target my coach and I agreed on into my bike computer, and I was going to stick to that number like superglue. The paradox of my plan was that the number was low. It was lower than I had expected. It was lower than it was at my first 70.3, and it was low relative to my power profile. It was so low that it meant I’d be doing what amounted to a zone 2 ride for the entirety of the bike leg.

The plan was predicated on the knowledge that the course was pancake flat, and that triathlons succeed or fail on the run. We would conserve energy on the bike, allowing my inertia to do most of the work, and hopefully get off the bike with enough in the tank to really drop the hammer.

So what the bike ended up being was a test of patience, rather than fitness. My heart rate stayed low, peaking only at the very start during the excitement of transition and climbing a tiny hill out of transition. I spent a lot of the time focused on avoiding drafting as much as I could, but it was pretty difficult considering that the roads were absolutely packed with riders. That forced me to surge occasionally, but it was okay because the course was so flat.

The first 20 miles flew by so fast that I was actually surprised when I saw the mile marker sign. At 30 miles I felt no worse; very comfortable and just cruising along. It was a strong contrast to my last race, where the 30 mile marker saw me doing pretty solid work. I began to get excited about the paradoxical plan as evidence in its favor continued to build. That naturally inclined me to want to push harder, but I redoubled my efforts to stay focused and in my target zone.

The highlight of the bike course by far was the Thermal Raceway, which is a private racetrack for cars that we got to ride around on. My watts went up on that section for sure, but it was a match that was worth burning. It’s a unique experience to ride your bike around a banked track with perfect pavement, designed for million dollar super cars. I had a lot of fun there.

The rest of the course was technically uphill but the gradient was so gradual, I barely noticed. I rode into T2 just 2 watts over my target. My family was cheering at the dismount line, which was a nice boost going into the start of my run.

After racking my bike and strapping on my running shoes, I started out on the final leg, to see if the contradictions would be resolved. Here I was, running in the heat and sun after training for months in the cold and snow. Here I was, having biked slowly on purpose to see if I could do a faster race. And here I was, after weeks of training at a jog, pushing my legs to go fast, and stay fast.

I have always run fast out of transition, because it takes a mile or two before my legs really feel normal and I can tell how my body is actually doing. At my first 70.3, I slowed that pace after the first aid station, feeling that I would have to conserve energy to make it through the run without shutting down. This day, though, I felt strong. I felt no such impending decline. I felt like I could hold the pace. So I didn’t slow down.

The run followed asphalt roads for a couple of miles before turning off onto a golf course, where it tracked around the greens on a winding, undulating path that was a mix of concrete, dirt and grass. There were no long straightaways, no places to hide from the course. It was highly dynamic and constantly changing.

A conclusion I had drawn from my first 70.3 was that I had been underfueled. This time, I ate and drank everything I could get my hands on during the run. I think I probably ate two or three whole bananas, a half at a time, plus several gels and all the coke, gatorade and red bull I could grab. I didn’t slow down during the aid stations; I didn’t want to lose my inertia. At one point I took a cup of ice, dumped it in my hat and packed it onto my head. The contrasts had never been more stark — at home I had been wearing winter hats to keep the snow off my head; today, I was deliberately packing ice onto my scalp.

It was a two-lap course which meant that I had to run agonizingly close to the finish line at around mile seven, only to have to turn around and do the entire thing one more time. Now I knew what to expect, though, and I knew where to push and where I could relax. Now all I had to do was hold my pace.

When the second lap of the course started to beat me, I focused on my family, waiting for me at the finish, and steeled myself in the resolve to make this all worth it. What was the point of asking so much of them, to support my training, to spend an entire day of our vacation standing around, if I didn’t make it worth it? I wasn’t going to slow down for anything.

The last couple of miles were hard and my pace started to slip a little bit, but I was still moving faster than I had ever really expected. I found my family just before the finish line, gave everybody high-fives, and then took it over the line. It was a personal best by a long margin, with personal records in every part of the race. I almost couldn’t believe it, but there it was.

If there’s one thing I learned from this race experience, it’s that you can’t always see contradictions as obstacles. Sometimes, they are puzzle pieces in a larger pattern that you can’t fully recognize until you’ve put it all together. You can’t always resist the things that don’t make sense; sometimes, you have to lean into them, make them part of your plan and see them through to the end. And that’s when you can find clarity.

We closed out our trip with a drive through Joshua Tree National Park, marveling at the natural beauty of the desert before boarding our plane to fly back into winter. With California behind us, it was time to look forward to a new year, and new contradictions.

Watch the video version of this race recap: